Stravinsky's Rite of Spring

Analysis by Joseph Straus

Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring is the most famous musical work of the twentieth century—as fresh and powerful now as it was when it was written, in 1913. This detailed analytical study consists of eighteen videos. The first five videos are general discussions of meaning, form, melody, harmony, and rhythm. The rest are a detailed, close analysis of the piece, scene by scene, block by block, and note by note. The author (Joseph Straus) is a well-known and widely published scholar of Stravinsky’s music. He is Distinguished Professor of Music Theory at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York.

Music performed by the London Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Simon Rattle. Used by permission of Naxos.

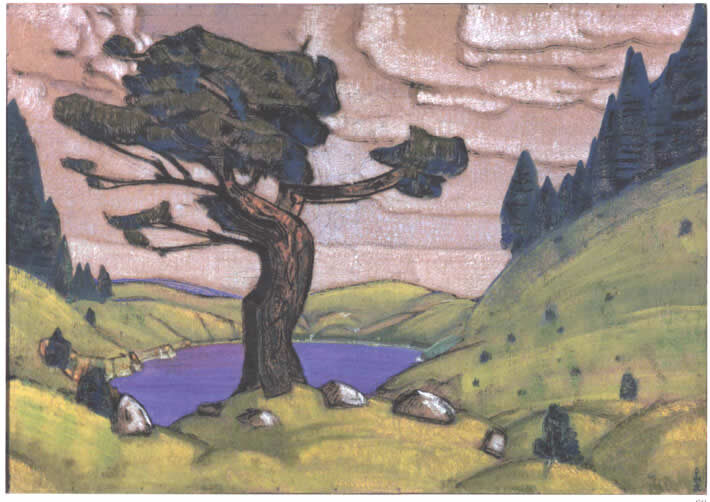

The visual images come from the Mariinsky Ballet’s performance based on Millicent Hodson’s recreation of Nijinsky’s original choreography and staging. Used by permission of Sputnik images.

Project completed with the help of: Ines Thiebaut (producer), Naomi Barretarra (consultant); and the wonderful editing skills of Drake Andersen, Annie Beliveau, Whitney George, Stephen Gomez, Scott Miller, Demi Nicks, Matthew Sandahl, and Lina Tabak.

Contact Us

Descriptions

Chapter 1: Meaning - The Rite of Spring is a ballet, rich in both dramatic and musical meanings. It deploys four groups of characters (Young Women, Young Men, an Old Woman, and Old Men) who move through four expressive modes: pastoral, military, religious, and wild dance. Dramatically, it moves through one symbolic day (from dawn to dawn) and one symbolic year (from spring to spring), culminating in a wild dance of death that is also a demonically transformed return to the opening music of the ballet.

Chapter 2: Form - The basic formal unit of The Rite of Spring is the block—a short, distinctive chunk of music that is sharply distinguished from the music before and after it. Discrete, contrasting blocks are combined to create the larger sections and scenes of the ballet. Within each block, the musical texture is stratified into distinct layers involving one or more melodies and one or more accompanying harmonic strands. The melodies are often amplified with additional melodic lines moving in parallel or near-parallel motion (planing).

Chapter 3: Melody - The Rite of Spring uses dozens of distinctive melodies. The melodies, which consist of short, repeated musical fragments, denote particular dramatic characters or situations (like the Old Woman’s Tune or the First Tribe’s Fanfare). The melodies move within a small melodic frame (usually a perfect fourth, tritone, or perfect fifth). They form expressive family networks, based on shared or transformed notes and intervals.

Chapter 4: Harmony - The harmonies of The Rite of Spring are often based on a stable perfect fifth, which can be filled in various ways, including as a major or minor triad. To these relatively consonant chords, a dissonant distractor (usually a semitone above the root) is frequently attached. Many harmonies involve a combination of two chords, each built on its own stable perfect fifth. The harmonies and melodies often combine to produce harmonic environments that can be described as diatonic, octatonic, or chromatic.

Chapter 5: Rhythm - There are five basic rhythm/meter types in The Rite of Spring: changing meter in a slow tempo; rapidly changing meter in a fast tempo; rigidly unvarying pulse in a slow tempo; rigidly unvarying pulse in a fast tempo; obscure, indeterminate meter. Each of these types has specific expressive associations with dramatic characters and situations. The complex, shifting meters can often be understood with reference to relatively simple prototypes, including surprisingly regular hypermeter.

Chapter 6. Introduction to Part One - The Rite of Spring begins with an instrumental introduction. The stage is dark and empty: it is just before sunrise on an early spring day. No human characters are present, and we hear mostly the sounds of the natural world (bird calls and shepherd’s pipes). The musical form of the scene is circular—it begins and ends with the same music—affirming its self-enclosed pastoral mode.

Chapter 7. Augurs of Spring - Augurs of Spring marks a radical shift from the Introduction to Part One. Dramatically, we shift from the pastoral to the military mode; from the natural world (with no dancers on stage) to the human world (populated first by male, and then by male and female dancers); from night to day; from a dark haze to bright clarity. The scene is in three large sections. In the first section, the Old Woman teaches divination to the Young Men. Amid the regular, march-like meter, punctuated with irregular accents, the expressive mode is military. In the second section (Dances of the Young Women), the pounding chords cease and the young women enter with their own distinctive tune. In the third section, men and women dance harmoniously together.

Chapter 8. Ritual of Abduction - The Ritual of Abduction is a scene of ritualized sexual violence in which young men forcibly abduct female mates. The expressive mode is military, with fanfares and hunting calls. It begins in wild swirl of octatonic harmonies and ends with a diatonic celebration of the men’s victorious hunt.

Chapter 9. Spring Rounds - The Spring Rounds marks a return to the pastoral mode of the Introduction to Part One, following the military-dominated Augurs of Spring and Ritual of Abduction. At the beginning and ending of the scene, we hear a simple, lyrical, diatonic melody—such a circular formal arrangement is itself an indicator of the pastoral mode. The two contrasting middle sections are a slow, solemn religious procession and a violent, military outburst, where one of the fanfare melodies from Abduction makes a reapparance.

Chapter 10. Ritual of the Two Rival Tribes - The Ritual of the Two Rival Tribes features games of mock combat between two groups of young men, each with its own distinctive military music (one of these tribes uses one of the fanfares from Abduction). In the middle of the scene, the young women attempt to intercede with the men, with a lyrical, feminine musical entreaty. By the end of the scene, men and women are dancing together in relative harmony, but that mood is interrupted by a strong musical premonition of the Sage, who is about to enter.

Chapter 11. Procession of the Oldest and Wisest One. Kiss of the Earth - The Sage’s procession was heralded at the end of the previous scene. Now, in the Procession of the Oldest and Wisest One, the Sage, attended by Elders, comes onto the stage and advances toward its center. In the extremely brief Kiss of the Earth, he lies flat and blesses the earth. This scene marks a musical shift in expressive mode from pastoral (female, young, human) and military (male, young, human) to religious (male, old, superhuman). The music is in a sort of primitive/religious learned style, involving not pitch counterpoint, but rather rhythmic and metric complexity—the closest approach to polymeter in the ballet.

Chapter 12. The Dancing Out of the Earth - The Dancing Out of the Earth, the final scene in Part One, is a wild, frenzied dance of life—orgiastic and animalistic. While previous scenes have often been oriented toward the diatonic or octatonic collections, in a pastoral, military, or religious expressive mode, this wild dance is oriented toward the whole-tone collection. Amid an explosion of musical and choreographic activity, we hear a whole-tone ostinato that rumbles through the whole scene—a sort of seismic underpinning.

Chapter 13. Introduction to Part Two - Part One took place during the daytime, from dawn through late evening. Part Two begins in darkness and lasts until dawn. The stage is dark and empty, just as it was in the Introduction to Part One. The music of the Introduction to Part Two is night music—dark, slow, mysterious. We are back in the feminized pastoral mode of the Introduction to Part One, and a long expressive voyage is set to begin again, one that will take us from pastoral, through military and religious modes, to the shattering dance of death with which the ballet concludes. This scene is in two sections, with a retrospective coda. The first section features what will become the main melody in the subsequent scene, the Mystic Circle of the Young Women. The second section features a sinuous two-part counterpoint (scored initially for two trumpets). A return to opening music at the end of a scene is one of the formal markers of the pastoral expressive mode.

Chapter 14. Mystic Circle of the Young Girls - In Stravinsky’s description, the Mystic Circle of the Young Girls involves young virgins dancing in circles on the sacred hill. The expressive mode is pastoral in a feminized dramatic and musical space, and the scene is thus linked in both expressive mode and musical content with Spring Rounds and the Introduction to Part Two. The scene is arranged in five sections. The first section presents the Mystic Circle melody in full, in a chorale-like setting. The second section presents a slighly contrasting second theme. The third section is a stately procession, with a religious feeling. The fourth section returns to the main Mystic Circle melody. This sort of formal return is a musical emblem of the pastoral. The fifth and final section is a transition to the next scene, marked by a sudden and violent change of expressive mode. It marks the moment when the sacrificial victim (the Chosen One) is “designated by fate.”

Chapter 15. The Naming and Honoring of the Chosen One - The peaceful, mystical young women have become Amazonian warriors, who menace the Chosen One (the sacrificial victim). The women have appropriated the military expressive mode, usually associated with the men, amid fanfares and hunting calls. The Chosen One remains motionless at the center of the stage while the other dancers exult in the forthcoming sacrifice with an outburst of wild, violent energy.

Chapter 16. Evocation of the Ancestors - Evocation of the Ancestors is in a religious expressive mode. The melody is chant-like in its murmured melodic oscillations—an incantation, hypnotic in its repetitions. The larger setting evokes a religious procession (companion pieces from earlier in the ballet are the procession in Spring Rounds and the Procession of the Oldest and Wisest). The tempo is slow, with a steady quarter-note pulsation throughout.

Chapter 17. Ritual Action of the Ancestors - In Ritual Action of the Ancestors, the dramatic focus remains on the Old Men (the Sage, the Elders, and the Ancestors) as they encircle the Chosen One. The expressive mode is religious: a solemn, somewhat exoticized, march-like religious procession. There is a flavor of the exoticized East here, both in the quality of the march and the slinky, chromatic melodies. It is a slow religious procession—a solemnization and consolidation of patriarchal power, consecrated by religious observance.

Chapter 18. Sacrificial Dance - Part Two of The Rite of Spring concludes, as did Part One, with a wild dance. But the Dancing Out of the Earth was an orgiastic dance of life; the Sacrificial Dance is a frenzied dance of death, with generic sources in the dance macabre and the operatic mad scene. A young woman is ritually murdered by the Old Men to propitiate the sun god and ensure fertility. Musically, the Sacrificial Dance is rich in references to the opening scenes of the ballet, usually in the spirit of radical transformation or demonic inversion: the musical materials of the pastoral opening return as essential components of this dance of death.